A presentation on innovative citizens’ initiatives: how they work, and what we can learn from them.

Update 2021: I made this presentation back in 2015. Omikron Project, our campaign that mapped all the grassroots initiatives I mentioned in this presentation, is now dormant. Some of the below links may no longer work.

It's still a relevant presentation though, as a primer on the possibilities of grassroots groups in general, how to map and categorise them (in any country), and ultimately stimulate them.

Side note: As recently as March 2021 on the Tim Ferriss podcast, the angel investor and entrepreneur Balaji Srinivasan talked about a future of networked community groups, delivering what government can’t. Well, it already happened – in economic crisis-struck Greece post-2009, as I document below.

Beneath the headlines on Greece’s upcoming elections and its ongoing crisis, there’s a quieter story happening. Across the country, hundreds of groups of regular people are stepping in where the system is failing, forming volunteer initiatives to tackle problems like healthcare shortages and education cutbacks, experimenting with alternative micro-economies and looking at new ways of addressing discrimination.

Last year with the team at Omikron Project, we documented these initiatives in our grassroots map. I presented our findings and thoughts on the topic at the Dutch embassy’s ‘Orange Grove’ space in Athens in December, discussing where things might be going and citing three case studies of groups that were setting great examples.

Since there’s now renewed interest in grassroots Greece thanks to this recent Wall Street Journal piece, I’m publishing that talk for anyone interested in learning more. A video of the talk is above, and an edited transcript with the slides, are below.

Transcript of presentation

I’m Mehran Khalili, a British-Iranian political communications consultant living in Greece. I work with international NGOs and activist experts, helping them to improve and evaluate their campaigns.

This is what I’ll speak about today: I’ll briefly introduce Omikron Project. Then I’ll talk about our grassroots map, and give you three good examples of grassroots groups.

Omikron Project

Omikron Project is one of my volunteer activities here in Greece. It’s a grassroots group itself, an art collective, a citizen-powered campaigning agency that exists to show the world the untold side of Greece’s crisis. We want to take Greek activism towards the outside world and improve how it’s communicated.

Here’s a picture of us having a meeting. It’s not in a co-working space or an office: it’s a bar, called Omikron Bar, and that’s why we’re called Omikron Project.

So when I say it’s a grassroots group, it really is. There’s no money, we’re all volunteers, everything we make is for free, and anybody can join. You can all become members of Omikron Project today if you want.

We’ve done several campaigns: videos, ads, quite a lot of media work, some presentations, exhibitions, research… Probably the thing we’re best known for is a short animated video called ‘Alex the lazy Greek’, which went viral and was shown on national TV in France and Germany. That video was made to tackle the ‘image crisis’ of Greeks, and the stereotypes of Greeks as lazy, corrupt, etc.

But today I’ll be speaking to you about another one of our productions: our grassroots map. Here it is:

Why make a grassroots map?

Our goal with the map was to document all the grassroots movements in Greece. For two reasons: to take a snapshot so these groups could get exposure, but also to burst the stereotype that Greeks are victims of the crisis. That they are somehow helpless.

Because in international media you always hear about things being done to Greeks, but you don’t hear much about what Greeks are doing at street level.

I have an international background and I’ve lived in several cities across the world. Yet I’ve never seen as much active citizenship as I do in Greece. So many people here are involved in causes outside their daily lives, their daily work. This is what we were aiming to show with the grassroots map.

What we mean by ‘grassroots group’

There are many definitions of what a grassroots group is.

For us, a grassroots group:

- Has an informal structure. There’s no legal framework.

- Has predominantly volunteers, as opposed to paid staff

- Can be either transient or ongoing. Grassroots groups get started, then collapse into activity, and that’s fine. Someone can be a member of multiple groups.

- Is open for others to join.

- Has a social or environmental cause as its purpose.

- Had no connection to a profit-making entity when it started.

This last point is important because it doesn’t preclude the idea that a grassroots group could get funding afterwards. But what we didn’t want in our documentation were groups that were founded, perhaps, when a big multinational said ‘here’s a load of money, make a grassroots group out of it.’

Why grassroots groups are important for Greece

In addition to being all these things, a grassroots group is also—this is really important, and I’ll come back to this idea later — a playground for ideas. There’s an American expression, ‘throw things at the wall and see what sticks’. This is what grassroots groups are about. They have a kind of start-up culture: give things a go, fail fast, iterate and try again. Instead of the more conservative way of starting something which is ‘OK, have I got all my pieces in place before I can start work? What’s my strategy? Where’s my funding? I’ve got to hire people’. Etc.

Bottom line: a grassroots group can provide people with a wonderful opportunity to simply try things, without the usual restrictions of a legal structure, funding, and so on.

In the same way, a grassroots group is like an incubator. Because some of these groups can really take off without the constraints I mentioned.

And lastly — and this is really important in Greece — a grassroots group is a forum where people can cross ideological boundaries and collaborate. Greece, as we all know, is unfortunately in a very polarised state. Grassroots groups provide a chance for people to come together — whoever they vote for, whatever they believe — and work on common projects.

Our grassroots map

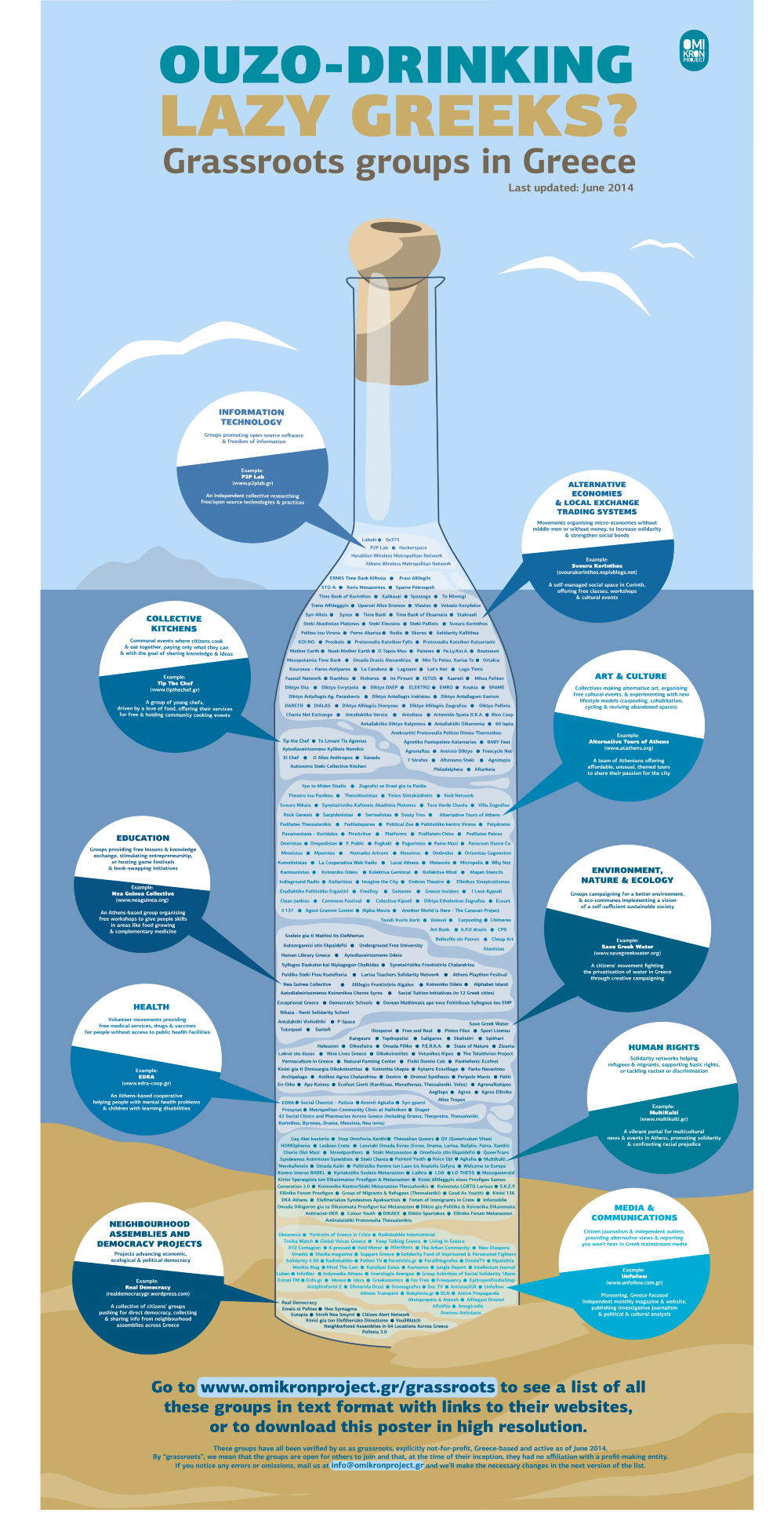

The map is titled “Ouzo Drinking Lazy Greeks” because as I mentioned earlier, we wanted to burst the stereotype that Greeks are helpless victims. There’s that question at the top of the map, and the answer is the map itself.

The map is a graphic, a poster; you can go to our website and download it in high resolution. You can print it, make T-shirts out of it, do whatever you want with it. You can put your name on it and say you did it: that’s fine with us, as it’s Creative Commons-licensed. It also has a companion webpage that has a list of links to all these different groups.

The map is the result of two to three months of research that we did, using the criteria I specified before. To the best of our knowledge, all the groups on this map were active in June 2014. (This is the second edition of map; the first was published in May 2013.)

On the map you see the different ‘layers’ of ouzo. (The first map was titled ‘Coffee-drinking lazy Greeks?’ and we had a big coffee glass, with layers of coffee.) Each layer — like collective kitchens, health, human rights, media and communications — contains groups that work on these specific topics. In the circles are example groups of each category.

Findings from the map

- Last year we found 238 groups. In the latest version, there are 415 groups. (We regularly get emails from more groups, letting us know they’re out there.)

- The vast majority of these groups were founded in the past few years. So if I were making leaps without having done the research, I could say that the growth of grassroots Greece is a response to the crisis.

- All the groups are addressing systemic problems in Greece.

- They are growing steadily in number. I’m sure the next version of the map, which we’ll make next year, will have more groups are on it. As many go inactive, new ones shoot up: the rate that these groups are being created is faster than the rate they’re disappearing.

- This build-up is happening very quietly. There’s not so much media interest in grassroots groups at the moment. And it’s happening with virtually no coordination: there may be two groups living next door to each other, that didn’t know they were working on the same thing. It’s very organic, very decentralised… it’s really quite a phenomenon. Yet as I said, nobody’s really talking about it.

Three examples of grassroots groups in Greece

Grassroots Greece today is very embryonic. Given that, it’s not the groups that necessarily have the most impact that we should be holding up and showcasing — it’s the groups that blaze a trail for other groups. Those that are examples of best practice. These three groups are exactly that.

Tip The Chef

Tip The Chef are a bunch of chefs that cater events for free. If you’re having a birthday party, wedding, whatever, they’ll come to your place, they’ll cook for you, serve the food, and if you like what they’ve done you tip them.

It sounds really simple, and indeed it is. But their story is what’s interesting.

You see, Tip The Chef was started about two years ago by four chefs who were very passionate about what they did, but couldn’t find proper paid jobs as chefs. Today, as a result of the buzz they’ve generated with Tip The Chef through social media and media coverage, they now all have properly paid jobs as chefs.

Think about what that means for a second. It’s a complete inversion of the usual model of ‘I don’t have a job, I’ve got to send my CV all over the place, I’m getting rejections’. And of course, we all know about the unemployment rate in Greece. We know there’s a crisis. But Tip The Chef…. they just turned all that on its head.

And if you can have Tip The Chef, you could have Tip The Anything. Tip The Masseur, Tip The Architect, Tip The Doctor, whatever. So what these guys have done is really interesting because they’ve set a great example in that respect.

Multi Kulti

Multi Kulti was started by a couple, Kostas and Ioanna. It’s an online guide to ethnic, multicultural Athens. You can go on there and find where to buy Cambodian beans in the city. Or see a host of interviews with immigrants talking about life here. You have a section where you see all the upcoming events that relate to multicultural Athens, and so on.

Looking at their site, as a resident of Athens, you think ‘I can travel the world in my own city!’. There’s simply so much going on.

But what’s most important about Multi Kulti is the reason it was founded: to tackle the problem of discrimination and racism in Athens.

Now, here in polarised Greece the typical response to these problems is ‘anti-fascist actions’, banning, censorship, and so on.

But what Multi Kulti does is different: it’s creative, positive, peaceful and educational. And that’s remarkable because there are so many other social problems here that could be tackled in a similar way — for a start, discrimination against any minority group. So Multi Kulti is really one to watch, because it’s a model that’s worth emulating.

Thalein

Thalein is a cooperative of 1200 families in Athens and beyond. It exists to connect these families with local producers. For a small fee, a family can be a member of Thalein and immediately get access to local produce — food, household items — that’s ethically sourced, quality checked, and most importantly is much cheaper than in regular shops. Basically, Thalein is slashing families’ supermarket bills.

Now, you might ask ‘How do they do this legally?’, since they’re cutting out the middleman. Here’s what’s great about Thalein: they worked together with the Greek government, with volunteer lawyers, to create a cooperative legal structure. So now, they’re operating completely legally.

And that’s really important, because if Thalein disappears tomorrow then another cooperative could adopt their structure and take over — and another, and another. For times like these in Greece, that could be vital.

Summary

So, just to recap:

- Tip The Chef: inverting the model of looking for a job

- Multi Kulti: tackling a social issue in a creative, peaceful, positive and educational way

- Thalein: reshaping the structure of the market, legally

All of these examples come back to the idea of grassroots groups as playgrounds, where you can throw things at the wall and see what sticks. Without a big business plan, without looking for funding, without a legal structure first. You just try it. These groups really are blazing a trail.

There’s so much more to do!

Before I wrap up, I just want to say: there’s so much more to do. All we’ve done as Omikron Project is take a photo. And there are others that have tried the same thing. It’s nothing; it’s superficial.

If we’re going to look at grassroots Greece in a serious way, we need to go deeper. We need to find out ‘Who are these groups? How many people are volunteering in them? Where are they based?’ etc. We need to survey them.

That needs money. That needs time. (Academics… does anyone want to do a PhD on this?)

We also need to enhance these groups’ visibility. Between each other, so they understand who is out there, and also to the outside world, in case they want funding. Rather than have a group with a brilliant idea collapse because they couldn’t get funding, because they didn’t have visibility… they should get that visibility.

And also, related to this, we need to establish a loose coordination of the groups here. By their very nature these groups resist centralised control, and I understand that, because Omikron Project is a grassroots group as well. But why not have a best practice sharing session for a bunch of groups that are doing the same thing? Why not bring these people together, so they can listen, share experiences, and perhaps strengthen each other?

And if we can do that, this quiet revolution… really could turn into something phenomenal.

I leave it with you. Thank you.